Park sees drop in the achievement gap

Graduation rates for people of color increased

April 28, 2016

After hearing about the recent rise in graduation rates for people of color, sophomore Alyssa Whetstine felt pride about Park’s success in closing its racial achievement gap.

“It makes me feel glad and proud that our school is working hard to decrease this gap,” Whetstine said.

Prachee Mukherjee, Park’s director of assessment, research and evaluation, said when she analyzed the school’s data, she found a gap between the performance of white students and of students of color.

“I have been doing this for over 10 years, and when I first started, I would analyze all the students achievement data. Very quickly I realized that I had to talk about race because no matter what grade level, no matter which subject and no matter what year I was looking at, there was this big discrepancy,” Mukherjee said.

Freida Bailey, a principal on special assignment for the achievement gap, said the reason the gap exists at Park is because of certain barriers.

“We have recent immigrant students coming into our district and they don’t know how to navigate, meaning that they come in and they don’t understand the steps of the state standards, the parents don’t speak the language,” Bailey said.

According to a study conducted by the Minnesota Department of Education, graduation rates increased 91.43 percent for black students, 94.12 percent for Asian students and 95 percent for Hispanic students in 2015.

Principal Scott Meyers said Park increased graduation rates by exploring and observing the achievement gap closely.

“Our high school has started to shift the way we view the achievement gap,” Meyers said. “In more recent years, we have started to explore the systems and beliefs that shape our classroom environments. High school teachers have been analyzing grading practices as well as delivery methods for lessons.”

Superintendent Rob Metz said the school’s new focus on racial disparity also decreases the gap.

“We have been decreasing this gap through racial equity works. Adults started to learn what race has to do with learning,” Metz said.

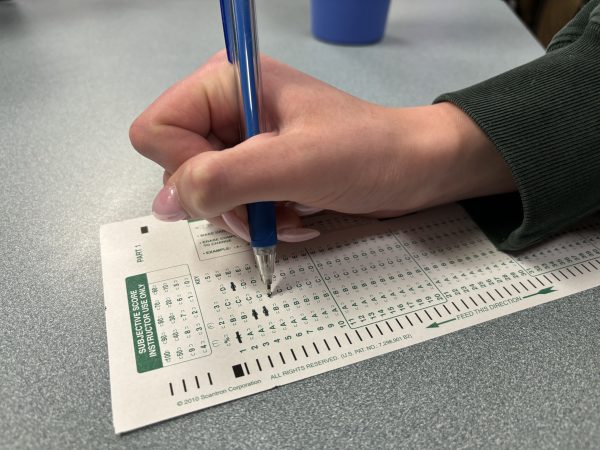

According to Metz, the school faces racial equity problems in the Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment (MCA) testing.

“If we were going to have an academic target, it’s MCA tests, and more specifically it’s third grade students. Last year, 60 percent of our third grade students were on track — we’d like it to be 80 percent,” Metz said.

Whetstine said making testing more inclusive to all backgrounds could help decrease the achievement gap.

“I think the school needs to find way to make testing more culturally relevant,” Whetstine said. “There’s a continuous argument and debate that these high state tests and the questions within the tests are primarily being seen through one cultural lens.”

Meyers said decreasing the gap helps diversify viewpoints in the future workforce.

“By reducing the achievement gap, we will infuse our workforce with a more accurate representation of the population. This should, in turn, help us consider more viewpoints for future decision making,” Meyers said.

Senior Iman Hills said she wants the school to continue close the gap to create balanced possibilities for students of all races.

“I think we should continue to decrease this gap because it gives everyone equal opportunity and makes it seem like our school isn’t having favorites,” Hills said.

Meyers said Park can continue to decrease the gap by making more changes to the current system.