Carbon dioxide threshold exposes cloudy future

When Dr. Ralph Keeling’s father began measuring atmospheric carbon dioxide in 1958, the level barely exceeded 315 parts per million (ppm). Last month, that number topped 400 for the first time in 4 million years.

The figure has received significant attention from Al Gore and U.N. Climate Chief Christiana Figueres to almost every major newspaper in the country.

However, Keeling, who directs the Scripps CO2 program, said this threshold is more symbolic than meaningful.

“Measured in small increments, we don’t see much change,” Keeling said. “But if we keep track of it across a long period of time and then hit these milestones, we say ‘hey, wow, we’ve come a long way.’”

Keeling said he sees a significant longterm trend in the measurements he and his predecessors take.

“Every year since I kept track and before I kept track, carbon dioxide has typically gone up,” Keeling said. “If you go all the way back to the dawn of the industrial revolution, levels were at 280 ppm.”

Keeling noted while the public may overplay the 400 ppm milestone, climate change is a growing concern.

“It’s really a gradual process when you view it within the context of year-to-year,” Keeling said. “But if you take into account how fast we’re changing the earth relative to natural phenomenon, it’s really quite rapid.”

Senior Trejon Baynham, like Keeling, said as the public now begins to see effects of carbon dioxide emissions, continued emissions will magnify them in future years.

“This is something that our children and our children’s children will have to deal with,” Baynham said. “I hope we get this issue resolved for them.”

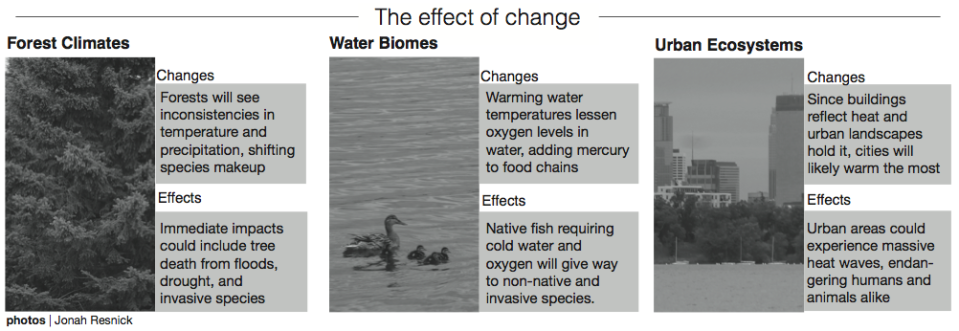

As scientists project a myriad of climate predictions, it can often be tough to pinpoint the local effect of such statistics, according to Keeling. However, a new Federal Advisory Committee Draft Climate Assessment Report indicated some of the tangible changes Minnesota could see in the coming decades.

Among these changes are milder winters, earlier springs, warmer lake temperatures, more severe weather and a 5 degree Fahrenheit rise in the state’s temperature by 2050.

With these climate changes come shifting migration patterns, fluctuating species complexion and eventual loss of cold-weather animals.

“Plants adapted for the Midwest now find themselves in a climate that’s almost certainly too warm, and plants from lower latitudes will begin to take over,” he said.

As scientists struggle to assess these impacts, the public has spoken out on behalf of Minnesota’s environment on issues from hydraulic frac sand mining to new cell phone towers in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Baynham said he encourages such protest to urge officials to take action over the warming planet.

“It is something that can be addressed, it’s just not a priority (in the government) for whatever reason. It’s something they need to take on,” Baynham said.

Keeling expressed optimism about rectifying the climate if the public rallies around the need for change in environmental policies.

“It requires unifying behind a political cause that requires less fossil fuels and more renewable energy,” Keeling said. We need to shift the whole playing field.”

However, sophomore Anna Huber said she believes the government needs to prioritize the economy over the environment during tough fiscal times in order to create environmentally sustainable businesses in the future.

“We cannot improve the environment until we improve how our economy is functioning,” Huber said.

Keeling said though future climate change may not be earth-shattering, it will have a major impact on humanity in the decades to come.

“Civilization developed under a stable climate system,” he said. “We don’t have a road map as to how civilization is supposed to function in a period of unstable climate.”

Keeling also stressed potential devastating effects of failing to curtail pollution.

“It doesn’t threaten life on earth,” Keeling said. “But that doesn’t mean it’s not terribly costly.”